Below are some resources and ideas which I hope you might find useful

Why Can’t I Change?

Often people feel stuck in life. They want to change in some way but can’t seem to move forward. But change is a process rather than a single decision. The Change Model, originally used in addiction therapies, can serve as a useful guide to help understand the change process. It sees us as all being at some point on a change cycle, a process that goes on continuously.

First we’re in pre-contemplation mode, maybe dimly aware of the problem, but with ample strategies, largely out of our awareness, to keep the issue at bay. At the next step, the contemplation phase, we become aware of what we might want to change, but we wrestle often unconsciously with the consequences of doing so. This is often where we are when we want to change but feel we can’t and that we’re agonizingly stuck. If change is not right for us at this time, we’ll go back to the pre-change phase. If we want to change, we go into preparation mode where we start planning. Then comes the change phase itself where we take action, then the maintenance phase where we sustain the change and incorporate it into our lives. Often we’ll relapse and go back to the pre-change phase, but we’ll have learned and grown from our experience. So if you’re feeling stuck, rather than blame yourself, it can be helpful to view yourself as being at a natural phase of a process that happens to us all.

Why Can’t I Make Decisions In Life?

It can feel intolerable to be wrestling with an important decision you just can’t make. Not only that, people often berate themselves because they feel they ‘should’ be able decide, making their turmoil even worse. But decisions are a process and often a difficult one.

Renowned American psychotherapist and theorist Irvin Yalom argues that humans can find decision making hard, because when we say yes to something, we have to say no to something else, often relinquishing an option that might not come again. It throws us, he says, up against a simple but frightening reality of life, that our possibilities and options are not limitless. Decisions, even when positive, involve loss. And he adds, decision making is a deeply lonely act. It brings home to us the fact that no matter how close we might be to others, we are also alone in the world.

Decisions can be so distressing that we routinely employ creative strategies to avoid them, a process which often out of our awareness. Yalom says these include: procrastinating so the decision is made by events, unconsciously manoeuvring others into making the decision for you (like withdrawing in a relationship so your partner feels so much pain that they leave), openly delegating the decision to someone, or my own particular favourite and a very common defence – devaluing the unchosen alternative. This means even though both options are fairly equal, we magnify the good features of the choice we’ve made and run down the option we’ve discarded, to avoid the pain of loss. But, he argues, social science research shows the way we make decisions is important. If we can face the discomfort and consciously make our own decisions we are more likely to see them through than if we let others or events make them for us.

Find out more about Irvin Yalom's writing here.

Why do I Keep Acting The Same Way?

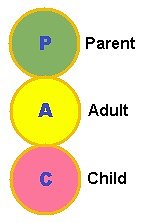

Often we find ourselves reacting to situations with feelings and actions which seem depressingly familiar. It’s as if they have hijacked us and taken us hostage. Why do we keep feeling the same old way, time after time? The PAC Model, (which stands for Parent Adult Child) is a helpful way of explaining how we get triggered into automatic feeling and behaviour patterns.

Developed in the US by Eric Berne, the founder of Transactional Analysis, a widely respected mode of therapy, it says we are always operating out of one of three ego states – Parent, Adult or Child (see diagramme below).

The Adult is our rational ego state, the state that allows us to think and determine action for ourselves based on what is happening in the present. Both the other ego states contain messages from the past buried deep out of our awareness. The Parent Ego State contains thoughts and feelings internalized from our parents, or other parental figures. It’s the part of us that feeds us with ‘shoulds’ and self-critical messages. The Child Ego State is the expression of emotions replayed from childhood, which we often experience now, in the present as intense, and 'coming out of nowhere'.

When we find ourselves getting upset in a way that seems familiar yet beyond our control, it’s because we’ve been triggered into a Child or Parent ego state, evoking old feelings, wounds and automatic behaviour. In therapy, we can work to uncover the patterns from our Child and Parent ego states that are no longer helpful, enabling us to have more choice over the way we behave.

Insomnia: why trying to control it doesn’t work

Chronic insomnia affects up to 25% of the population. Often people say they need to ‘control’ or ‘get a grip on’ or ‘battle’ their insomnia. If they just fight it hard enough, put in place more strategies to outfox it, then it will be banished. But this is a strategy which doesn’t work..…

There’s an old saying – you can put yourself to bed but you can’t put yourself to sleep. And this is true – as human beings we can do many things but force ourselves to sleep is one not of them. With chronic insomnia, it is our anxiety about the insomnia, which causes our sleeplessness. Every night, our anxiety levels rise and therefore our adrenalin levels, fuelled by the fear that we won’t sleep. We become locked in a vicious cycle, anxiety fuels insomnia, which fuels more anxiety and so on.

Sleep physiologist Guy Meadows’ useful and sensible best seller The Sleep Book teaches that the way to leave insomnia behind is not to struggle against it but to accept it as a fact of your current life, thereby allowing you to let go of the anxiety that’s causing it. Meadows’ programme is about doing less rather than more. Instead of arousing anxiety levels by struggling with complex rituals, he advises a mindfulness based approach, which is about being willing to simply lie in bed, notice and experience the fear of not sleeping, so you can weaken its hold over you. If you have been having no luck battling against your chronic sleeplessness, Meadows’ refreshing approach, based on years of treating insomnia, is a very helpful place to start.

The Vulnerability Paradox

Psychology researcher Dr Brene Brown’s book Daring Greatly argues passionately and wittily for the transforming power of vulnerability. She investigates the belief so many of us hold, that vulnerability is weakness and our vulnerable feelings must be defended against and squashed down at all costs.

Instead, based on decades of her academic research into how people thrive in life, Brown makes a down-to-earth and compelling argument for the Vulnerability Paradox

This is the idea that, far from being a weakness, allowing ourselves to experience as Brown puts it: “the uncertainty, emotional exposure and risks that define what it means to be vulnerable”, is an act of strength and courage, one allows us to challenge what holds us back in life. Leaning in to our vulnerability rather than turning away from it is, according to Brown’s research, a stance automatically adopted by people with high resilience and resourcefulness. And it also perfectly describes the process we go through in counselling and therapy, where allowing and exploring our difficult feelings can help us to move forward.

Are You A Rescuer?

When we get into conflict we often find ourselves replaying familiar roles. But what we also do is switch roles constantly throughout the conflict, playing the roles of persecutor, victim and rescuer, keeping the drama going, rather than resolving the issue. There’s a well-respected model that explores this phenomenon – it’s called the Drama Triangle.

Invented by psychologist Stephen Karpman, it illustrates the destructive power games we can play in relationships (see the diagram below) by flitting between three roles. The victim’s stance is ‘poor me’, they feel powerless, and unable to take responsibility. A victim stance invites someone to step into the role of persecutor or rescuer. A persecutor stance is controlling and angry, insisting that it’s all someone else’s fault (again, a convenient way to avoid personal responsibility). A rescuer is an enabler, taking responsibility for the victim, or angry persecutor. It’s subtly superior, and provides the pay-off of taking the focus off the rescuer’s true anxiety and needs by focusing on others’ problems.

Though we all have a favoured stance in relationships, in a conflict with others we’ll find ourselves hopping around the drama triangle, becoming alternately victims, rescuers and persecutors as we try to unconsciously get our needs met.

It’s something we all do. But, awareness of when we’re locked in a drama triangle can help us stand back assess what we’re really doing and make choices about how to resolve conflicts in a more adult way.

Angela Holden,

Counselling and psychotherapy in Tooting, south west London,

19.07.16

Are You Compulsively Busy?

You’re under stress. What do you do? For many of us we simply instruct ourselves, harshly, to work harder, to do more. Soon we’re running on cortisol, there’s a physical speeding up, along with a racing mind, swirling with obsessive thoughts. We’re living in the future, plotting and strategizing, trying to neutralize potential threats coming down the track. This is what US psychologist and author Tara Brach calls: “addictive doing”. This is our protection strategy, the way we cope with the discomfort of stress, and dissociate from the pain of the underlying feeling that we’re in some way falling short.

What Brach says we do is go into “a trance of unworthiness” where we see we’re not accomplishing what we’d like and beat ourselves up by trying to do more and more. Before we know it we’ve become very small, busy versions of ourselves, unable to tap into our full potential and experience the aliveness of life. And it makes us feel more stressed, not less.

I find Brach’s regular podcasts, which mix wisdom, scientific research, exercises in personal inquiry and self-compassion, excellent resources for bringing self-awareness to the unconscious, automatic patterns we all adopt in life to get us through difficult times. And with self-awareness comes more freedom and choice as to how to relate to our challenges. Her talk on bringing awareness to doing is here.

Angela Holden,

Counselling and Psychotherapy in Tooting, south west London

05.07.16

Managing anxiety

I have been impressed by a practical down-to-earth book which explains what is going on in our bodies and minds when we feel anxious and gives some useful strategies for managing the symptoms.

Anxiety affects many of us to some degree or another. Sometimes specific life events can cause it to escalate, while some of us are more prone to chronic anxiety and worrying than others because of our family backgrounds and biochemistry. In How To Master Anxiety, authors Joe Griffin and Ivan Tyrell explain something that I think is crucial to understanding how to manage anxiety, the negative feedback loop that develops between our minds and our bodies that keeps anxiety going and escalates it. It’s simultaneously a mind and body issue - a normal response that has got out of control.

When we’re assaulted by what we perceive as threats from the outside, our nervous system goes into a state of panic and high alert, we’re running on adrenaline, and this very state fuels ever more anxious, fear-based, catastrophising thoughts, which in turn make our nervous systems even more hyper-aroused. And so on, until our anxiety is buzzing around, looking for any new thing to latch onto.

What’s useful about this book is that it stresses the importance of managing the symptoms of anxiety by quieting both our bodies and our minds – through relaxation techniques like 7/11 breathing and cognitive behavioural exercises, aiming at putting thoughts in perspective. While I believe chronic anxiety as part of your personality style, your way of coping in the world, can benefit from being explored and worked through in depth in counselling and psychotherapy, I also believe practical resources such as self-help books can be helpful in managing down our symptoms of anxiety.

Angela Holden,

Counselling and Psychotherapy in Tooting, south west London

24.05.16